This is part 4 in my series about the impact of technology on education. The previous post regarding research was profound. If you would like to read the whole series, you can start with Part 1, which provides an overview before subsequent posts dive deeper into the nuances.

What if the problem was never the tool, but the lack of sustained support? Or support from the onset?

For years, classrooms have been flooded with platforms, programs, and promises. New tools arrive with excitement, urgency, and often good intentions. Teachers are (sometimes) trained briefly, then sent back to their classrooms to “make it work.” Sometimes there is no training, and expected to “make it work”. When outcomes fall short, frustration follows. Fingers point in every direction.

But perhaps the most honest explanation is also the least controversial: we asked educators to transform instruction without giving them the time, space, or support to truly learn how to do so.

One-Time PD vs. Sustained Learning

Most teachers recognize this pattern immediately.

A new tool is introduced. There’s a short training – here’s what it does, here’s where to click – and then: Go use it. Sometimes there’s follow-up, but it’s often months later and/or focused narrowly on features, not instruction. Other times, PD becomes so repetitive that it feels disconnected from classroom reality.

The spacing matters, just like it matters with our students. When training sessions are too far apart, teachers naturally fill in the gaps themselves. They figure out what works (and what doesn’t) through trial, error, and time; often without a shared pedagogical vision guiding those decisions.

Add to that the reality that many schools roll out multiple new tools or curriculum adoptions at once, sometimes with little dedicated time at the start of the year to learn them deeply. And sometimes there’s too much information coming at the beginning of the school year. The result isn’t resistance, it’s overload.

There has to be a better way.

Pedagogy Must Come First: We Can’t Pretend the Clock Rewinds

In theory, most educators agree: pedagogy should come before platforms, curricula, and pacing.

In practice, that train has already left the station long ago.

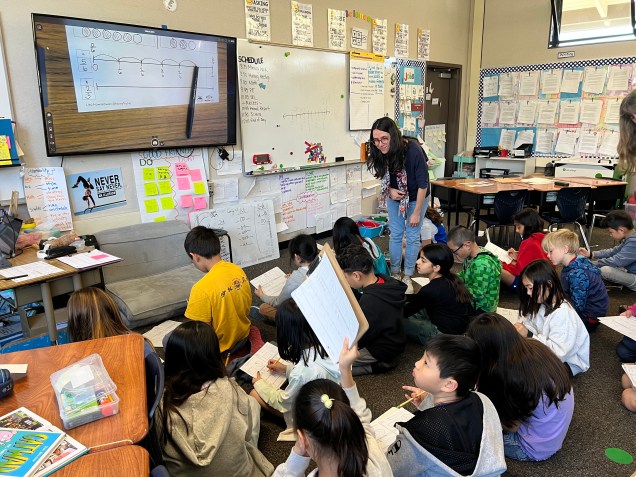

Teachers are knee-deep in platforms that were adopted years ago. Pedagogy often became secondary, not because educators didn’t care, but because survival required learning to manage the tool with students in the classroom in real time before reflecting on how it shaped instruction.

So the question isn’t Should pedagogy come first?

It’s How do we re-center pedagogy now, given where we are?

One possible answer isn’t adding more tools, but pressing pause. Limiting new adoptions. Creating space for a pedagogical reset using the platforms already in place. Asking not What else do we need? But how can we use what we have better? Or how can I use what is already available? How will it help me/my students?

This isn’t easy. It can feel overwhelming. But if the goal is student thinking, understanding, and transfer, not just task completion or student compliance, then the work is necessary.

What Meaningful Tech PD Actually Looks Like

I know, this is a loaded question. We want it, we know we need it, but are often loath to attend, myself included. This is especially true when it’s district-provided. Why is that? (That was more of a question to myself, no sarcasm, just a real thought/question)

If professional development is meant to change classroom practice, it must be manageable, relevant, and immediately useful.

That starts with focus. If a district introduces three new tools, meaningful PD might center on just one—and even then, on one or two high-leverage instructional uses, not every feature. Depth matters more than breadth. I’m a fan of showing how it is relevant to you, right now.

PD also needs to be differentiated. Some teachers are ready to explore advanced applications. Others need a strong foundation. Meeting teachers where they are isn’t a luxury; it’s how learning works. The trick is to do this well. I’m not sure what the answer is, but I know it should be a goal.

And perhaps most importantly: teachers need to be able to use what they learn immediately. I am passionate about this point. If something isn’t implemented within a week, it often never will. This isn’t a failure of commitment; it’s the reality of teaching in a system filled with mandates, assessments, and competing priorities.

Ongoing support matters too. Not once a semester. Not when schedules allow. Consistent coaching, collaboration, and feedback help teachers refine their practice at a pace that feels sustainable rather than rushed.

Teachers invest in what moves their students forward. When the impact is visible, the motivation follows.

The Cost of Not Investing in Teacher Learning

When professional learning is shallow or fragmented, classrooms tend to drift toward extremes. Again, this isn’t a criticism of teachers; it’s a reality.

In some cases, technology becomes a digital babysitter, students consume, click, and complete without deep thinking. That’s the compliance factor. In others, technology is avoided altogether. Of the two, opting out may be the more responsible choice, but it still leaves potential untapped.

A middle ground exists.

When teachers are supported in learning how and why to use tools, technology can amplify good pedagogy rather than replace it. Tools that provide immediate feedback, surface misconceptions, or help analyze student thinking, like Snorkl or Wayground, can lighten the instructional load while keeping learning active and visible. I know I keep bringing up these two tools. They are ones I have available in my district. There are other tools that achieve the same things.

But even the best tools can’t compensate for a lack of investment in teacher learning.

A Shared Responsibility

This isn’t about blame. We are where we are, and reflection is necessary.

Teachers didn’t ask for constant change without time to adapt. Administrators didn’t design systems to overwhelm. Policymakers didn’t intend to sideline pedagogy. Everyone involved is operating within constraints and doing what they feel is best.

But if we want classrooms where students think, explain, and truly understand, then professional learning can’t be an afterthought. It has to be central to how we implement change.

Teachers and students deserve better than “I have to do this.”

We’ve tried that. It doesn’t work. It’s time we try something different.

So, my question to you is, if professional development were designed around learning rather than compliance, what would change, for teachers, for students, and for the system as a whole?

Coming Next:

If professional learning is the bridge between research and practice, the final question remains: what does balance actually look like in real classrooms? In the next post, we’ll step back to examine what sustainable, thoughtful technology integration can, and should, feel like for teachers and students.