Post 5 in the Teaching in a Digital Age series. See previous post.

After research, reflection, and hard truths, the question many teachers are left with is a simple one:

What can I actually do, right now, without adding more to my plate?

It’s the question we are often asking ourselves. This post isn’t about sweeping reform or perfect implementation. It’s about small, realistic shifts that rebalance technology use, protect teacher energy, and put learning back where it belongs: with students. As they say, the person doing the work is the person who is learning.

Start With Choice Boards (Without Overthinking Them)

If you’ve read my blog long enough, you know that I am a fan of choice boards. But choice boards don’t have to be complicated or beautifully designed. In fact, many teachers already use a version of them without calling them that: a “must do” and “may do” list.

A simple way to begin, and what I do:

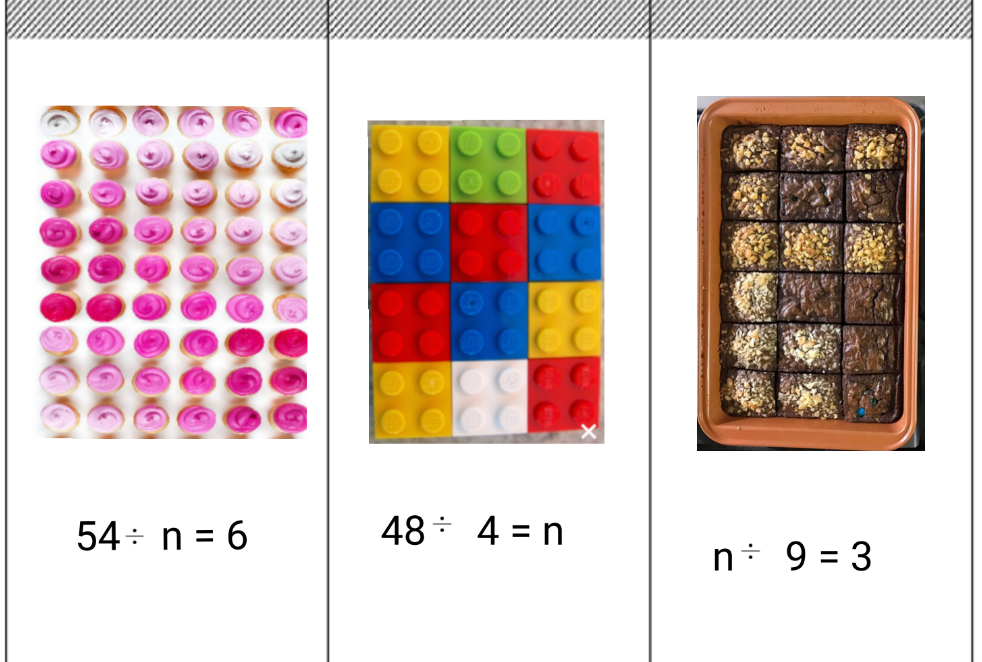

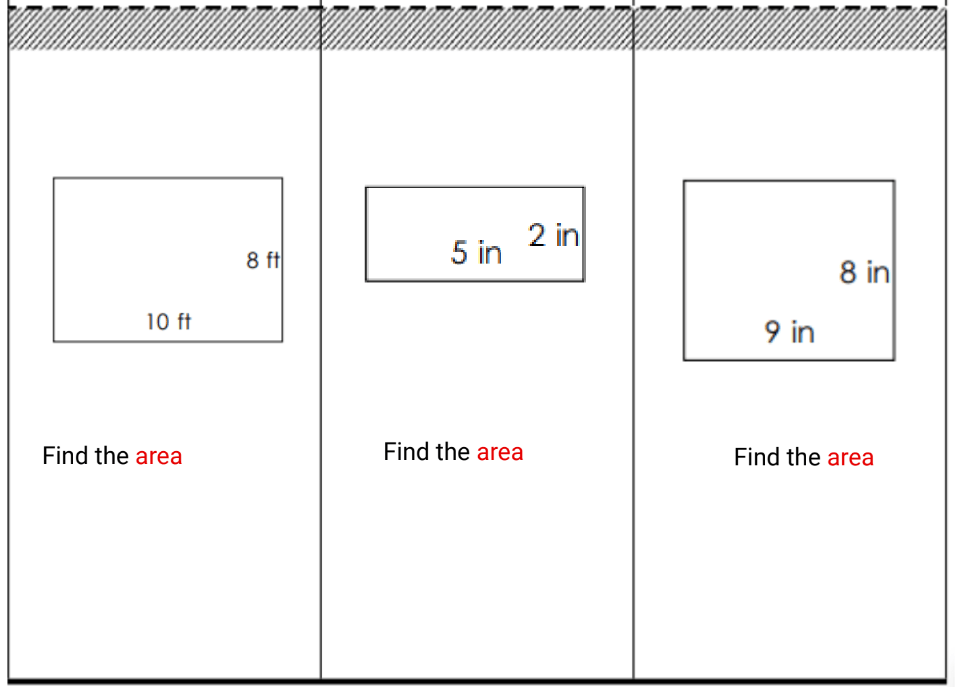

- Choose the skill you want students to practice or master.

- List familiar ways students can show understanding (write, draw, explain, build, record).

- Decide how students will share—digitally or not.

That’s it. I’m a fan of having students share their work, not just turn it in.

The focus stays on skills and mastery, not the tool. Technology becomes an option, not the driver. A student might choose to draw a model, make a poster, record an explanation, design a game, or write a short reflection. Over time, these low-tech options can naturally lead to digital creation, but only when it makes sense.

Choice builds ownership. Ownership builds engagement.

And none of this requires a new platform (unless you want one).

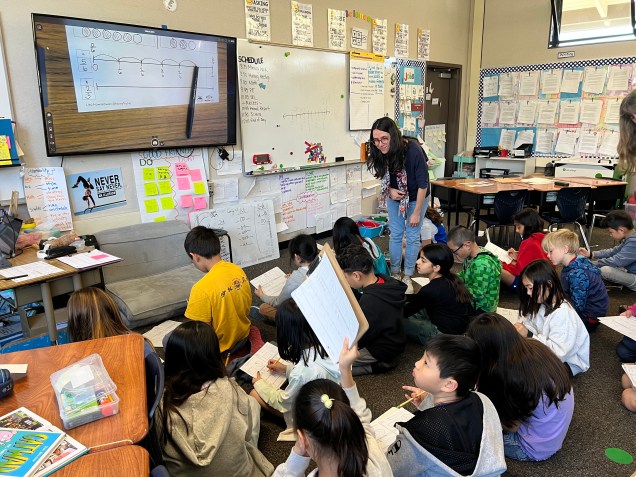

Lean Into Student Explanation

It’s easy to feel like there’s no time for student talk. There’s content to cover. Pacing to manage. Standards to meet. It all can feel overwhelming at times.

But explanation, oral, visual, or written, isn’t extra.

It is the learning. I know it sounds simple, and the time can feel like extra, but it’s really not. Remember: start small.

Short, structured opportunities for students to explain their thinking, turn-and-talks, quick presentations, sketch-notes, and exit explanations, strengthen understanding and surface misconceptions faster than silent work ever could.

These practices also align naturally with ELD standards, but they benefit all students. Being able to explain clearly, listen actively, and respond thoughtfully is a skill worth protecting instructional time for. And when a student can explain the material clearly, you know they understand it.

Sometimes the most powerful move is simply to stop and let students talk.

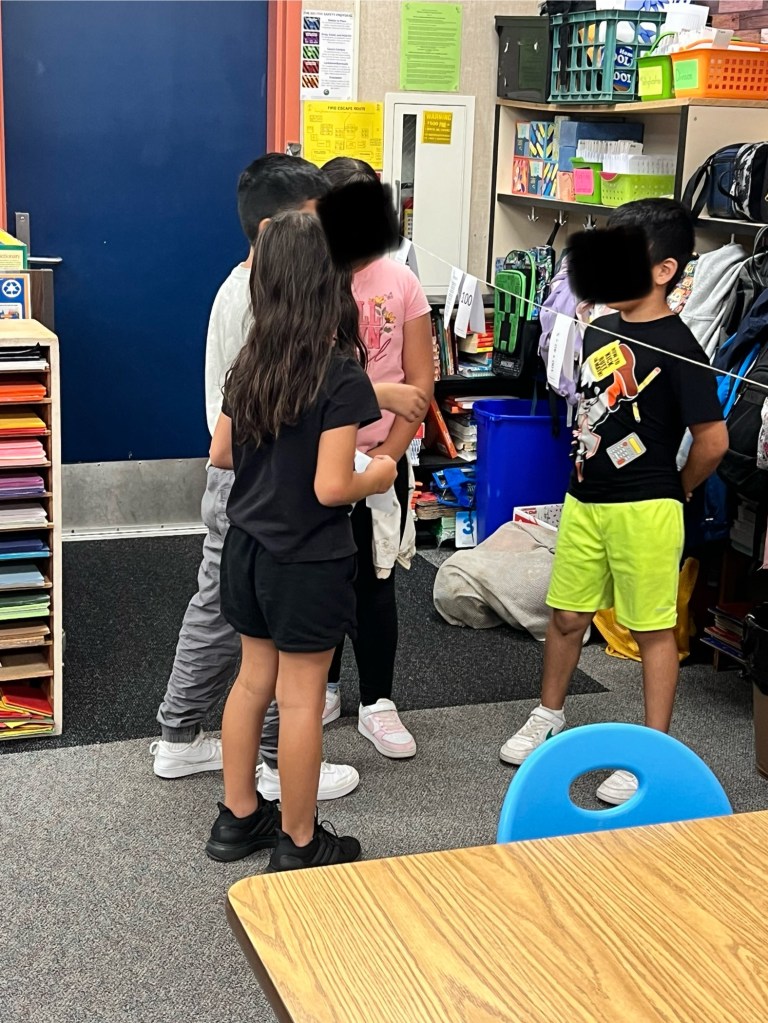

Build Simple Routines That Shift the Cognitive Load

When students know:

- where to find materials

- what success looks like (success criteria or proficiency scales)

- how to make choices

- where finished work goes

…the cognitive load shifts from the teacher to the learner.

This isn’t about losing control; it’s about creating systems that run themselves. As an instructional coach, I have found that having systems in place is valuable for teachers. It lowers your stress and makes for a more peaceful classroom. Once expectations are clear and routines are established, students work more independently, collaborate more naturally, and take greater responsibility for their learning.

That shift frees you up to do what matters most: conference, observe, intervene, and support students who need it most.

You already do much of this instinctively. The key is being intentional and letting go just enough. And if you are thinking to yourself, “I already do all of this,” then you should feel validated.

Start Small (Really Small)

This might be the hardest part.

Teachers are learners. We read blogs, attend conferences, watch webinars, and leave inspired. The temptation to do all the things is real. I am one of those who want to do all of the things right away.

But change works best when it’s edited. And I get it, I have trouble editing. But here are some things I have learned and would like to share with you.

Choose one shift:

- One new routine

- One way students explain

- One choice opportunity

Let students become comfortable. Let yourself adjust. Once it’s working, then layer in something new.

Doing too much too fast overwhelms students and teachers alike. Sustainable change is slow, and that’s not a flaw. It’s the point.

Where MathReps and EduProtocols Fit

Strategies like MathReps and EduProtocols fit naturally into this work, not as mandates, but as examples.

They emphasize:

- showing thinking over choosing answers

- explanation as learning

- repeatable routines that reduce planning load – This is probably the biggest bonus.

Used thoughtfully, they can support production without requiring perfection or constant novelty. But they’re options, not requirements. What matters most is the principle behind them: students actively making sense of their learning.

A Final Thought

You don’t need a new platform. (And if you’re like me, you want the newest, shiniest tool)

You don’t need a complete overhaul.

You don’t need to do more.

You need permission—to start small, to focus on thinking, and to build a classroom that works for you and your students.

That’s where balance begins.

So, what is one low-lift shift you could try this week that moves students from consuming to producing, without adding to your workload?