Getting Started with MathReps in Your Classroom

Here’s a suggested way to get started:

- Choose the Best Template:

- Browse through the available MathRep templates and select the one that aligns with the specific skills your students need to practice.

- Consider their proficiency level and the learning objectives you want to achieve.

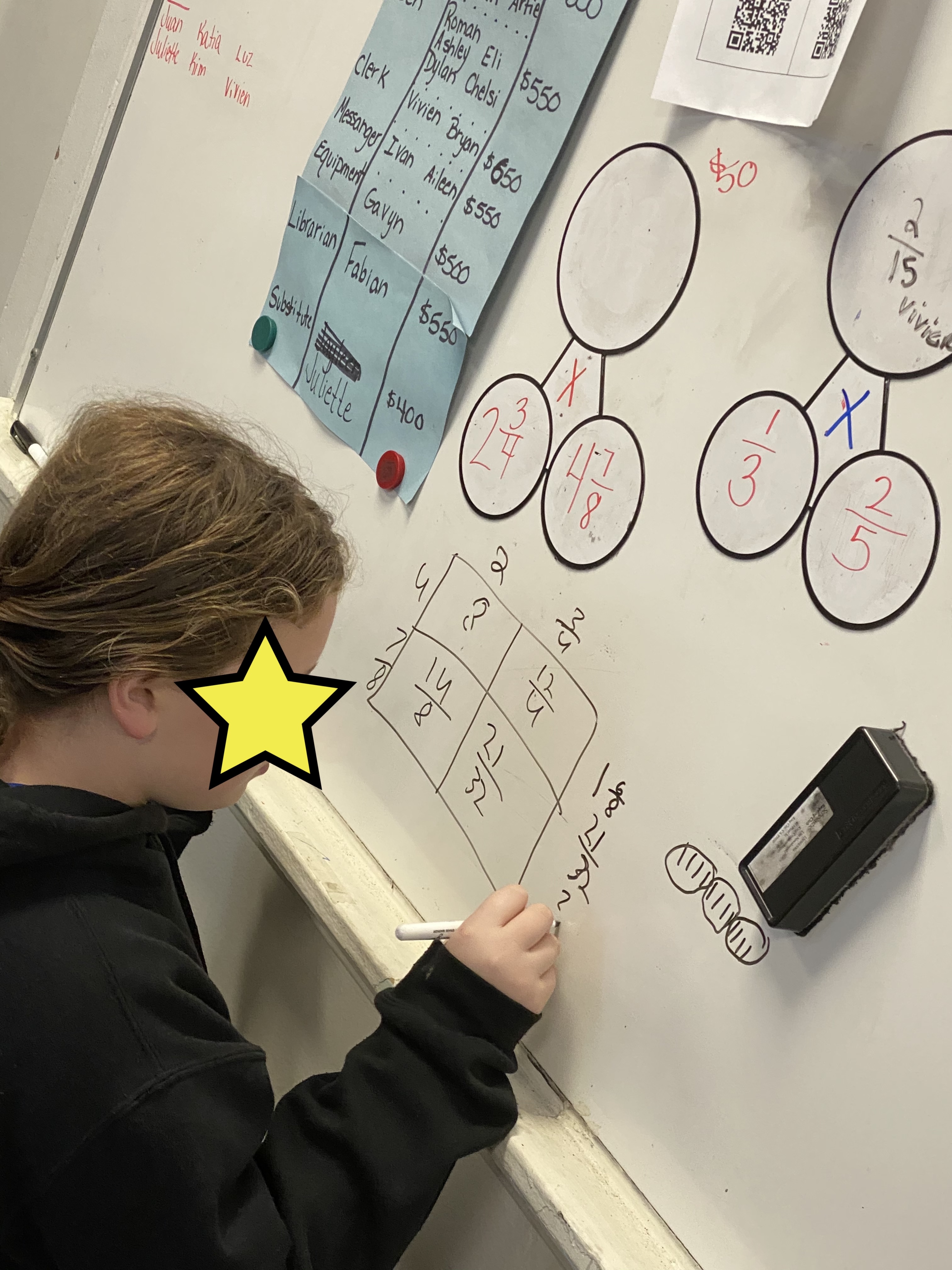

- Introduce the Template and Work Through It Together:

- Start by providing a brief explanation of the MathRep template to the class.

- Guide your students through the process of completing the MathRep a few times together.

- Break down the steps and demonstrate how to approach each section of the template.

- Encourage students to ask questions and clarify any doubts they may have.

- Daily Practice for the First Week:

- During the initial week, make MathReps a part of your daily math routine.

- Assign the MathRep as a class activity and have students complete it with you.

- Spend time reviewing and discussing the answers as a class, this emphasizes immediate feedback.

- Use this opportunity to address misconceptions and reinforce problem-solving strategies.

- Independent Completion in Subsequent Weeks:

- After the first week, assign MathReps for independent completion by each student.

- Encourage students to work on MathReps at their own pace, within a given timeframe (following Parkinson’s Law).

- Provide support to struggling students while encouraging higher achievers to challenge themselves.

- Checking immediately with students provides crucial feedback.

- Weekly Assessment to Track Class Mastery:

- Every Friday, use the MathRep template as a weekly assessment tool.

- Collect and review completed MathReps to assess student progress and understanding.

- This will help you identify areas where the class as a whole may need additional support or where mastery has been achieved.

- Transitioning to New Templates:

- Once your class has demonstrated mastery of the current MathRep template, consider introducing a new template with new skills.

- Gradually increase the complexity and challenge of the MathReps to keep students engaged and continually progressing.

- Review

- Spend time reviewing previously used MathReps templates.

- After students have become familiar, but not proficient, with a new template, spend a week reviewing a previous template.

- This allows for the learning to ‘stick’.

Remember, adapt these steps as needed to suit the unique needs and learning environment of your classroom. MathReps can be a powerful tool for promoting mathematical proficiency and fostering student growth. Happy math practicing!

So what’s the big deal with 92%? A lot when it comes to having 3 weeks off and the likelihood that none of my students practiced their multiplication facts.

So what’s the big deal with 92%? A lot when it comes to having 3 weeks off and the likelihood that none of my students practiced their multiplication facts.

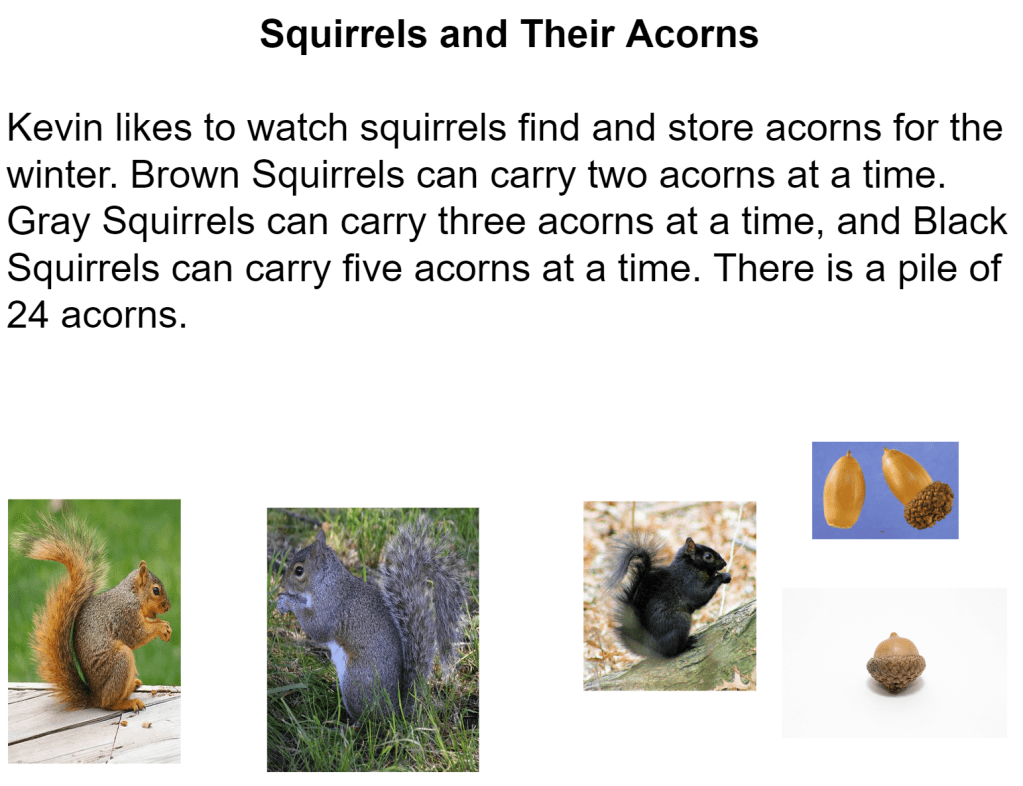

This is a sample I created for my class. My intent was to review some basic math concepts while having fun. The rules are simple:

This is a sample I created for my class. My intent was to review some basic math concepts while having fun. The rules are simple: